Two years ago we learned about a few people dying in a far-off land and soon were engulfed in a world-wide pandemic that has killed more than 6 million people world-wide and nearly 1 million people in the U.S. alone. Now we are seeing people die every day in Ukraine and wonder whether the violence will engulf the whole world and kill millions, or even precipitate a nuclear war that could wipe out humanity.

How we view the events in the world, the story we tell ourselves, has a lot to do with the actions we take and whether there is a peaceful solution or an endless conflict. I recently wrote an article, “Beyond the Myth of David and Goliath: How We Can All Support Ukraine in Bringing About Lasting Peace,” highlighting the dominant story that we see in the news media and how it may blind us to finding a peaceful solution to the invasion that is now in its fourth week.

I find myself going in and out of three different internal emotional states. Some days I feel totally depressed, engulfed by the inability of humanity to solve the life and death problems we create for ourselves. When I become depressed I feel powerless to even imagine a way out that doesn’t make the problem even worse. I feel inadequate and despair thinking about the world my five children, seventeen grandchildren, and two great grandchildren will inherit.

But on other days, actually most other days, I feel energized and hopeful. I remember that the world has seen dark times and in past and humanity has found ways to come through to the light. I think of the end of apartheid in South Africa, the success of the Civil Rights movement, the #MeTwo movement, Black Lives Matter, and the election of the first Black president of the United States. I remember the women’s movement and how it has freed both women and men from the restrictions that told each sex how we must act and how we must not act and gave us all permission to be who we really are.

And on some days I just want to forget the world of violence and war and just celebrate St. Patrick’s Day at the pub with my friends and family as we did the other night. I want to escape from the human world of conflict and pain to hang out with the trees and listen to the sound of the birds. I want to listen to the whisperings of the ancient redwood tree in my back yard that speaks of a different kind of wisdom and invites humanity to listen. I long to go to sleep and be reborn into a world where all our problems are fixed and I would have the perfect life I was promised in fairytales.

But I’m a writer. So whatever kind of day I’m having–depressed, hopeful, or just having fun in a now moment–I write. Today I’m inspired by my community of friends and colleagues doing “men’s work” and two people and organizations who have provided me inspiration and guidance for many years. I’ve known and worked with Riane Eisler, author of The Chalice & The Blade and many other books, and her Center for Partnership Systems, for nearly thirty-five years. I’ve been inspired by her simple, yet clear, contrast between two systems. In The Chalice & The Blade she says,

“The first, which I call the dominator model, is what is popularly termed either patriarchy or matriarchy—the ranking of one part of humanity over the other. The second, in which social relations are primarily based on the principle linking, rather than ranking, may best be described as a partnership model. In this model—beginning with the most fundamental difference in our species, between male and female—diversity is not equated with either inferiority or superiority.”

In Ukraine we see a clash between two different systems, one based primarily on domination. The other based primarily on partnership. We also see a difference in two kinds of masculinity, one exemplified by Russia’s Vladimir Putin is clearly one of domination and the other by Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky is primarily one of partnership.

Another colleague who’s work offers two contrasting systems is Otto Scharmer. Scharmer is a Senior Lecturer in the MIT Sloan School of Management and co-founder of the Presencing Institute. He chairs the MIT IDEAS program for cross-sector innovation and introduced the concept of “presencing”—learning from the emerging future—in his bestselling books Theory U and Presence, the latter co-authored with Peter Senge and others.

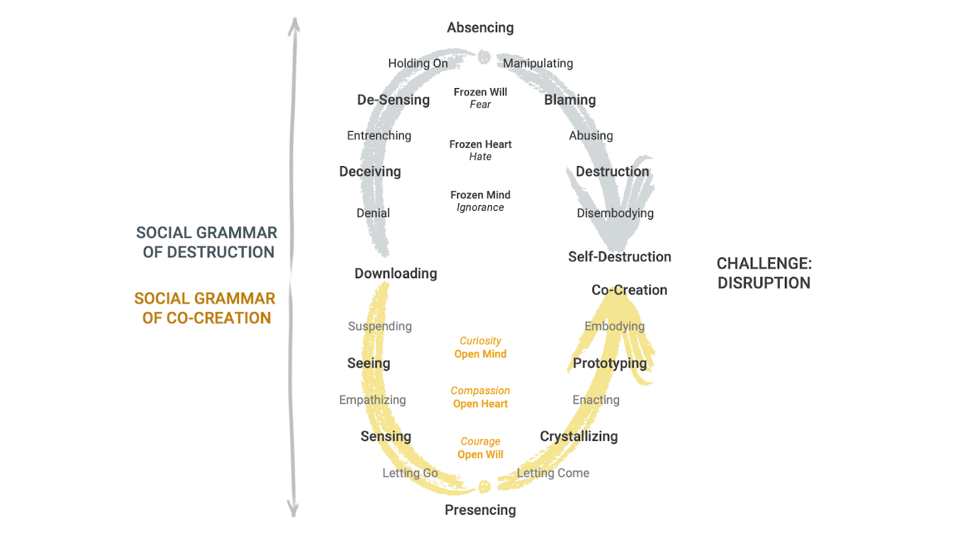

Scharmer has recently written two important essays that contrast two systems, which have great similarities to the ones Eisler presents, one he calls absencing, the other presencing. In the first essay, “Putin and the Power of Collective Action from Shared Awareness: A 10-Point Meditation on Our Current Moment,” he says,

“I invite you to join me in a meditative journey on the current moment. We start with Putin’s war in Ukraine, unpack some of the deeper systemic forces at play, look at the emerging landscape of conflicting social fields, and conclude with what may well be the emerging superpower of 21st-century politics: our capacity to activate collective action from a shared awareness of the whole.”

Scharmer goes on to offer an historical perspective on Vladimir Putin, how his increasing isolation from other people makes him more dangerous, and its relevance to the present moment. He describes Putin’s blind spot as his failure to predict the degree of Ukrainian resistance or the unified support he has received from the West. After Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, Angela Merkel, the then Chancellor of Germany, talked to President Putin and reported to President Obama that, in her view, Mr. Putin “had lost touch with reality.” He was, she said, “living in another world.” This mindset of fragmentation, isolation, and separation is nowhere more strikingly visualized than in the recent pictures of Putin alone at one end of a massive table and his team (or occasionally a head of state), at the other end.

“This isolation (from your team, from people who think differently, and eventually from reality), is obviously at odds with the increasingly volatile complexity of our real-world challenges today,”

says Scharmer.

“Even though Putin, Commander-In-Chief of one of the most powerful armies in world history, may continue to win all the military battles for a while, it feels as if this separation from reality — that is, the reality of his own blind spots — have already sown the seeds of his demise. His blind spots seem to be the strength of civil society and the power of collective action from shared awareness.”

In the David and Goliath myth one side is perceived as virtuous and honest, while the other side is seen as treacherous and evil. In this view only the “bad guy” has blind spots. But Scharmer also describes the blind spots of the West. “Let me be more specific,” says Scharmer.

“IF it was that clear that Putin planned to invade Ukraine (as US intelligence had predicted for many months), and IF it was equally clear that NATO could never directly step in (without risking an all-out nuclear war), then WHY was it so impossible for the West to simply agree to Putin’s often repeated primary request: a guarantee that Ukraine would not be allowed to join NATO (just like Finland, Sweden, Austria, and Ireland, all of whom are members of the EU but not of NATO)?”

Scharmer goes on to highlight the blind spot of President Biden and the U.S. response to the invasion.

“What were Western — particularly US — leaders thinking? What was the rationality of the Western two-point strategy against Russia: (1) decades of ignoring and discounting Russian objections to the various waves of the eastward expansion of NATO, and (2) betting that Putin would change his behavior when threatened with economic sanctions?”

In the second essay, “Putin and the Power of Collective Action from Shared Awareness,” Scharmer continues by describing the contrasting systems and how we might move from absencing to presencing.

“I invite you to look at the current situation through the lens of emerging future possibility — the lens of a social field shaped by the grammar of transformative co-creation,”

says Scharmer.

One of the main dangers of a seeing the world as a battle between Goliath and David is that we neglect important aspects of history and fail to see our own blind spots or see opportunities for truly hearing other points of view. As Scharmer’s model suggests, we get locked into a mindset where:

- Our minds become frozen in ignorance.

- Our hearts become frozen in hate.

- Our will is frozen in fear.

Seeing the world through the lens of presencing, by contrast:

- Our minds become open and curious.

- Our hearts become open to compassion for the suffering of everyone on all sides of the conflict.

- Our will becomes open to inner courage and a willingness to find true partnership, to rebuild trust, and find common ground.

Otto Scharmer concludes with these inspiring words:

“In this exploration of two different social grammars, we learned that the future does not just depend on what other people do. The future on this planet depends on each and all of us and our capacity to realign attention and intention on the level of the whole. As Noongar Elder, cultural guide, and scientist, Dr Noel Nannup reminds us: ‘All we need to do is to have a piece of the path to the future that is ours; and we polish that and we hone that.’ Co-holding and co-creating that emerging path to the future puts us in a very personal relationship with our planet and with our shared future.”

We all have a choice about which of these two ways of seeing the world we want to embrace. I’ve learned over the years that where we place our attention greatly influences what we create. If we focus on our fears, our view of reality tends towards domination and absencing. If we attend more to our care, compassion, and love, our view of reality tends towards partnership and presencing.

Humanity truly is at a tipping point. None of us know the outcome, but each of us can choose which side of the balance we put our minds, our hearts, our will, and our action, on.

I look forward to your comments and knowing what you are doing in the words of my colleague Charles Eisenstein to bring about the “world our hearts know is possible.” Come visit me at MenAlive.com and check out our Moonshot Mission for Mankind and Humanity.